The Eucharist of Judas: Sacramental Theology on Spy Wednesday

This week and especially tomorrow – but at every celebration of the Eucharist - we remember how it came to be that Christians affirm that Christ is truly present here, received and known in the breaking of the bread.

But today is not Maundy Thursday, it’s Spy Wednesday – the day we consider Judas. Ponder then the possibility of eucharistic theology through the eyes of Judas. Just as the Gospels tell us that even Jesus’ immediate personal presence in history did not guarantee understanding and love, so too we find that the Eucharist itself can become a means where we may misunderstand and betray, as well as find and embrace our Christ.

The Gospel of John, like the others, presents Jesus performing a symbolic action at the fateful meal with an instruction to continue it as a means of connection with him. But John presents the parting act of Jesus as the washing of his friends’ feet. “[H]e poured water into a basin and began to wash the disciples' feet and to wipe them with the towel that was tied around him”. “For I have set you an example,” Jesus says, that you also should do as I have done to you”. This will be read tomorrow, along with the familiar account of him take bread and wine as his body and blood, and can be seen as a kind of ethical lens to interpret the other story; Jesus’ self-giving, his servant ministry, a sign in his and their bodies of what bread and wine become, and what they make those of us who receive them.

But the Gospel this evening, the passage immediately following the foot-washing, depicts a more acute problem of eucharistic ethics, because it presents a eucharistic story not of self-giving love but one of mutual recrimination and betrayal (wait - was I at that meeting recently?).

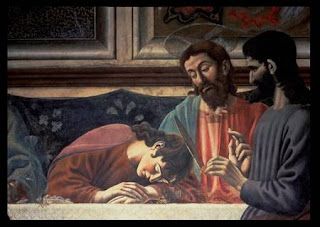

Judas is a participant at the supper, in what tradition considers the first Eucharist. Judas is identified as betrayer in the very fact of his partaking in the sacred meal, and even as the first communicant of the great high priest: “[Jesus] gave it to Judas son of Simon Iscariot. After he received the piece of bread, Satan entered into him”. The point is underlined four verses later; “after receiving the piece of bread, he immediately went out. And it was night.”

This first metaphysical theology of the eucharist contains a very high or realistic doctrine of spiritual presence, but it’s the wrong presence: “Satan entered into him.”

I know those of you doing Anglican Way 1 will immediately think of Article XXIX: “The Wicked, and such as be void of a lively faith, although they do carnally and visibly press with their teeth (as Saint Augustine saith) the Sacrament of the Body and Blood of Christ; yet in no wise are they partakers of Christ: but rather, to their condemnation, do eat and drink the sign or Sacrament of so great a thing.”

Neither the article nor the Gospel suggest that faith itself creates the sacrament, but rather they acknowledge that the incarnate God present in the sacrament will not act coercively in us. The eucharistic Christ is the foot-washer, the betrayed friend, the crucified one; he is not going to make us become his disciples, but will, in the fragile elements of this eucharistic meal, make himself vulnerable to us, even to our misuse, while allowing himself to be in us and us in him.

The Eucharist is a sacrament of Christ’s body, but not a substitute for discerning it or otherwise becoming it. Judas’ failure to discern Jesus’ body was already signaled in his rejection of Mary’s action at Bethany, which we heard in the Gospel two Sundays ago. Our Gospel tonight glances back at that story, when it suggests the others thought Judas had gone out to give money to the poor, part of the detail shared in the Bethany meal story. And while there is no mention, in this Gospel, of Judas betraying Jesus for thirty silver coins, he had betrayed him at Bethany already by objecting to Mary’s valuing of him at more than three hundred.

Jesus’ eucharistic presence is neither a magical or automatic fact whereby grace will come, regardless of how we value his or others’ bodies; yet neither is it merely an idea, just a sign or symbol of ourselves and whatever measure of sharing and caring we are up for this week. He is truly present, as he was really with both Mary and Judas, and yet only received by one. The eucharistic reality he offers is true presence here in bread and wine that offers to reveal and create a different true presence in us, in each other, in the world and all its vulnerable bodies.

He invites us at every Eucharist to consider his embodiment in relation to our own, and not just to consider but to share in receive, take, eat it; to receive his broken and vulnerable body and make it a part of our own, and our bodies part of his, "that we may evermore dwell in him, and he in us."

Comments

Post a Comment