Getting Dirty: Easter, Rogation, and the New Creation

|

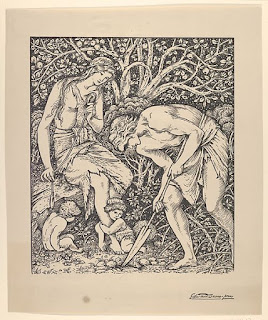

| Carl Hentschel after Edward Byrne-Jones, "When Adam Delved"; Metropolitan Museum, New York |

At that time, these words were given and heard with solemnity, even perhaps dread; dust or dirt introduces Lent as a time of reflection on the shape of our life and particularly its finitude. In that context, the reminder of our connection with the earth is solemn or even fearful. “Dust” here has a particular sort of poetic bleakness; but we could just as well say “soil” or “dirt." All these represent our origins and destiny.

Yet so much depends on context. The historian of religion Jonathan Z. Smith tells a story of working on a farm while preparing to attend an agricultural school:

"I would have to rise at about a quarter to four and fire up the wood burning stove, heat a pan of water and lay out the soap and towels so that my boss could wash when he awoke half an hour later. Each morning, to my growing puzzlement, when the boss would step outside after completing his ablutions, he would pick up a handful of soil and rub it over his hands." (Map is Not Territory, 290-91)

When the callow youth eventually confronted his boss with the oddity of this gesture, the farmer responded:

“Don’t you city boys understand anything?…Inside the house it’s dirt; outside it’s earth. You must take it off inside to eat and be with your family. You must put it on outside to work and be with the animals” (Map, 291).

While we sometimes speak of what is “soiled” or “dirty” to connote what is out of place, our relationship with dirt is not simply negative. In the Book Genesis (see Gen 2), the story of creation is presented as the formation of the human person from the earth; that first human is named Adam, meaning in Hebrew earth, dirt. The connection with dirt and dust is not a threat only, but a miracle; we are made of the same stuff, the atoms and molecules that are in all other things, yet also fearfully made, crafted in the divine image. Striking as our mortality is, the more striking thing is that matter itself is, that it is wondrously and beautifully ordered, that we are a part of it, and we are given the extraordinary and daunting gift of its care and use - all this being made of dust, of dirt.

And yet in human history as in Genesis, our stewardship is plagued by disobedience from the outset - our affinity with the earth is forgotten, and we treat it and each other not as wondrous creatures bound by loving purpose, but as objects to exploit. Ironically we talk about treating people like dirt; but dirt is the stuff of creation, and itself demands a kind of reverence it rarely receives, in the industrialized world at least.

We can also make things “dirty,” but this has little to do with actual dirt. The comic Lenny Bruce once said "You can't do anything with anybody's body to make it dirty to me...you can do only one thing to make it dirty: kill it. Hiroshima was dirty."

This unlikely source of theology speaks a deep truth, exemplified also in the story of Jesus. In Christ, God shares in being dirt, not merely in the benign sense of material existence, but in the malign sense of becoming subject to rejection, defilement, and degradation. The cross of Jesus is God’s submission to our awful sense of the dirt; on the cross, Jesus becomes dirty, a "curse" as St Paul puts it, to deliver us from sin and death (see Gal 3:13).

If Lent encouraged us to consider the limits of our dirt-based creatureliness, and the need to reconsider how we make each other and the world itself “dirty”, Easter does something different.

The resurrection of Jesus is not the defiance or refusal of the world of dirt, in the sense of embodied material existence, but is its renewal and transformation. Ancient Jews expected a resurrection of the dead as sign of the end of all things; recall Martha and Jesus speaking at Lazarus' tomb, close to the fateful events of Easter; he said to her, ‘Your brother will rise again.’ Martha said to him, ‘I know that he will rise again in the resurrection on the last day.’ Jesus said to her, ‘I am the resurrection and the life.’

The scepticism of many of his contemporaries to Jesus’ resurrection initially lay less in its mere possibility, as in the audacious claim that this man whose body had been cast aside as rubbish, as dirt, was in fact the new Adam. Martha reflects the widespread Jewish belief that there would indeed be a last day and that resurrections would happen, but at that time; but by rising, Jesus is not just proclaiming his own victory over death, but the inauguration of that new world here and now, rather than only in an unknown future.

Today’s reading from the Revelation to John is part of the seer’s vision of a “new heaven and a new earth.” He describes a world transformed, even without the institutions of religion and government, but still with dirt, apparently; for even though there is nothing unclean in this new heavenly Jerusalem there is "the tree of life with its twelve kinds of fruit, producing its fruit each month; and the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations.”

The resurrection of Jesus puts our earthy physicality in a new light. Jesus does not reject or transcend the dirty world - rather he reveals and restores its purpose, and ours. We are still made from the dust of the earth, but the earth is now also a sign of God’s promise, that extends even beyond the immediate fate of our embodiment. Like Jesus, we do not escape or transcend the earth; we find instead, and even become, the signs of the new earth.

Baptized, we are born to this new life. In the Eucharist we receive food from the earth of this world, transformed into the food of the new world, where all are fed equally. Now every tree hints at the Tree of Life, every creature glows with the glory of God, and every fellow-human is a miracle of divine promise, made from dirt and destined for glory.

Today is Rogation Sunday, the beginning of a week that has traditionally involved prayer for seasonal weather and successful crops. This year I invite you to consider getting dirty for Rogationtide; to put your hands in the soil of a creation made good, and which is also a sign for us of a new world, where the tree of life grows. Plant a seed, or a tree; tread with care and awe on the soil of this fragile earth; love one another, feed one another. Thus we will prove followers of the risen Lord, in whose body the old earth and the new meet.

Comments

Post a Comment