Seven Last Words: 1. Father forgive them; for they know not what they do (Luke 23:34)

Then Jesus said, ‘Father, forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing.'

Each evangelist offers a similar account of what Jesus did on the cross, but a somewhat distinctive account of what he said. This devotion based on the seven sayings gleaned from the different narratives thus embodies the character of the Gospel and the Gospels - a diversity appropriate to the variety of human experience, and a commonality appropriate to the depth of human need.

.

|

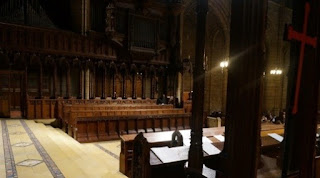

| The Chancel of St Thomas' Church, New York, on Good Friday. |

Of these seven sayings the great Franciscan theologian St Bonaventure said:

Our Vine uttered seven words while he was raised upon the cross. They are, as it were, seven leaves that are ever green. Or it you prefer, your Bridegroom can be thought of as a kind of lute, which is an instrument that consists of a piece of wood shaped like a cross. His body, in place of the strings, is stretched across the wood, but the seven words are the individual strings (Vitis Mystica).

Other medieval commentators drew parallels between the seven words from the cross and seven wounds sustained by Jesus - counting them as the four nail piercings, the crown of thorns, the lash, and the spear.

But the seven days and acts of Creation in particular invite comparison and reflection with these words. Each of Jesus’ seven words from the Cross can be understood as a creative act, as a new divine work. In the narrative of Genesis chapter 1, God also creates by utterance seven times: “let there be…”. Here too, Jesus - the divine creative Word made flesh – speaks, and the world is made anew.

The idea that Jesus does anything on the cross is remarkable, because of the nature of a cross. A cross of course is designed or suffering; but in particular it was designed for immobility, constraint, and passivity. The anguish of the cross was, as much as or more than the agony of the nails, a matter of being prevented from acting, being rendered an object and not a subject, becoming a mere thing to be acted upon.

And yet this cross is for us Jesus’ great work, his creative masterpiece. More than any miraculous exercise of power over nature or human infirmity recorded in the Gospels, more than any profound teaching we have from him in longer and challenging words than these ones, it is this story, this time and place, where he does his greatest work. Bound and nailed tight and still, he re-makes the world and us, and just as in the beginning creates by word.

Jesus gets the hardest work done first, we might say, with the first word. “Father, forgive them.” A man has just been nailed to a cross by violent occupiers, and is being jeered at by his compatriots. A few words of resistance or judgment, of foreshadowed comeuppance, might not have made us think much less of Jesus. He was capable of such frankness, after all - “woe to you scribes,” and so on. But this is not what we find here.

Rather, as Luke (and Luke alone) tells us, Jesus begins his saving work with “Father, forgive.” And note that this is not just some general magnanimity either; he says “Father forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing.” Well, they actually seem to know pretty well exactly what they are doing, in the usual sense; the trials of Jesus, his appearances before colonial and local authorities across the preceding day, have involved numerous points at which the various perpetrators, active and passive alike, could have stopped the momentum of violence. In our terms, they were intent and malign, and knew just what they were doing.

This is not, however, just a sort of over-weaning kindness on Jesus’ part. In fact in another, deeper sense, they do not know what they are doing, for they have mistaken who he is. As St Paul says, “none of the rulers of this world knew [this hidden mystery which God foreordained before the ages for his glory], for if they had known, they would not have crucified the Lord of glory” (1 Cor 2:7-8).

What Paul suggests here is that they do not know what God is doing in Christ and on the cross. What they think they are doing - keeping order by making an example of a trouble-maker - in fact becomes another sort of thing. Those for whom he prays are the unwitting co-workers with Jesus in this labor of forgiving the world; and he blesses them, movingly, strikingly, by including them explicitly, even and specifically his enemies, in the scope of God’s extraordinary mercy. For of course he came to forgive those - all of us - whose actions have made these events take place. Forgive them; forgive us.

Forgiveness is hard work, work that we often find beyond our powers. This example may seem beyond us to emulate. Some early Christians regarded Jesus as stretching forgiveness beyond the bounds of good taste with this saying; there were ancient manuscripts of Luke’s Gospel from which this verse was omitted, excised by scribal correctors who (as such often do) thought they knew the mind of God better than Jesus did, or at least than Luke did. It is the only one of these seven sayings that has been subject to such textual difficulty, and therefore apparently the hardest to accept and make sense of. The objection may have been sharpened by the difficult relationships between Christians and Jews in the early centuries; the idea of forgiveness for those labeled Jesus’ enemies in particular seemed unpalatable. But this saying stands, in its significance and in its authenticity too.

We must accept that God’s forgiveness does not work according to our sensibilities. Here at the cross, even the cruel and the vile are offered the reality of a divine embrace that we simply cannot comprehend. And if it is hard to accept that God’s forgiveness extends to those whom we despise and blame for our own ills and the world’s, it is or should be as hard and as important to know that we ourselves are included in it. In the end, we may not need so much or only to comprehend how inexplicably wide God’s mercy is for others, but to understand, little by little, that God’s mercy has comprehended us.

Comments

Post a Comment