Ratzinger and Rowan: Leadership and Theology

|

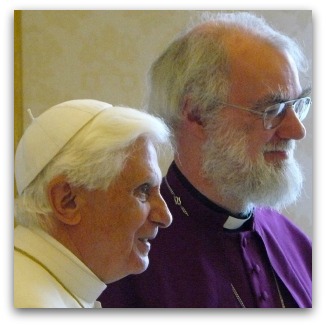

| Rowan Williams and Pope Benedict XVI (Eureka Street) |

Williams and Ratzinger, although a generation apart in age, had more in common than academic credentials when they came to office. Both are steeped in the theology of the early Christian writers known as the Church Fathers, and although Williams focussed his Oxford doctoral studies on eastern Christianity, he also has a deep and sympathetic engagement with Augustine of Hippo, on whom Ratzinger had written at Munich, before going on to his second doctoral thesis (as is normal in Germany) on Bonaventure.

Both have also used this training in the depths of Christian tradition to do theology in a way that involved new insights and potential controversy. This is reasonably well-known on William's part; his famous essay "The Body's Grace" remains one of the most important starting points for a revised assessment of homosexuality that is more than lazy indifference to sexual morality in the name of inclusion.

It may seem a more surprising assessment of Ratzinger, who at least from mid-career had acquired a reputation for being a guardian of orthodoxy rather than an explorer of its frontiers. His Bonaventure thesis had however been savaged by an examiner for alleged traces of "modernism", and he was one of the theological advisers at the Second Vatican Council.

If he subsequently leaned towards tradition more clearly, is fairer to say that Ratzinger has, like Williams, always written and acted with a deep commitment to the truth as well as to his perceptions, right or wrong, of the needs of the Church.

Yet Ratzinger came to the papacy, as far as many in the West were concerned at least, as threat more than promise. Having headed the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith for most of John Paul II's papacy he had a reputation as a watchdog, who had acted against theologians such as Leonardo Boff and Anthony de Mello as well as seeming to slow or reverse the momentum for change initiated at the Council.

Williams on the other hand was a figure greeted with hope by Anglicans but also by others, across traditions, who anticipated that his combination of grounding in tradition and openness to change would be reflected in his role as Archbishop of Canterbury. He had not, however, had to exercise comparable authority, or at least to occupy a role relevant to the whole Anglican Communion, before that.

Now that Williams has returned to academic life and Ratzinger's retirement has been announced, it is tempting to commit both their reigns to the category of failure, and debate mostly the nobility or otherwise of their inability (or unwillingness) to bend lurching structures or less gifted minds to their own wills. This would not, however, be the whole picture in either case.

Their shortcomings, real or perceived, have tended to cluster around the Church as institution and the way it treats its members. Williams struggled to hold together the disparate views of the various national Anglican groups, on human sexuality in particular. Ratzinger's Church and its challenges were altogether different, but he struggled to master a Vatican bureaucracy whose disarray has become more apparent with time. Opinion is divided about whether the increased attention he paid to the reality of clergy sexual abuse has made sufficient difference to be a matter of great credit to him.

There will be those who see this real or perceived failure of the theologians as implying a need for a different kind of leadership; Justin Welby's elevation to the see of Canterbury arguably reflects not only his personal virtues, but a shift towards managerialism, given his previous corporate experience. If the Cardinals perceive what the faithful in general and the world at large do, they too will surely respond to the present needs of the Roman Catholic Church in terms that allow for some sort of new broom.

This may however be to do the departing prelates some injustice. The deepest problems faced by these Churches have to do with the changing environment in which they find themselves, and the growing secularism of the West in particular. Both Williams and Ratzinger have made important contributions of an "apologetic" nature - that is, related to the defence of faith as possible and powerful. Williams' dialogues with such as Philip Pullman and Richard Dawkins have been important and public examples. The outgoing Pope has not been willing or able to contend on similar ground - his important Regensburg lecture in 2006, which was a thoughtful reflection on religion and power among other things, caused an outcry after a misleadingly-excerpted quote from a Byzantine emperor was attributed to the pontiff himself.

His encyclicals and other writings deserve more attention than sound bites or mainstream media have allowed, and will continue to get it from the thoughtful among Roman Catholics and others. His books on Jesus have been popular, but while they involve an important critique of reductionist interpretive methods, it is hard to see them going beyond mere traditional piety in the actual working out of a picture of Jesus.

Ratzinger's powerful defence of reason and critique of relativism are more important than his own quick jump from these to intractable positions about a set of difficult moral questions allows many to see. Like Williams, he is capable of defending and promoting a Christianity which is intellectually plausible and challenging, not only to obvious forms of moral relativism but also to injustice and environmental irresponsibility. His pontificate has not been a time when many beyond the Roman Catholic Church took him seriously in this regard - we could hope that relinquishing the burden of office may free him to be read, and heard, again.

[First published in Eureka Street here]

Reports from inside Rome in recent years have Benedict XVI saying things like, “Well, now I am going to go and talk to my friend Rowan.” A fuller account of this friendship waits to be compiled by a close analyst of Vatican and Lambeth manners. It is fascinating to ponder the fact that Rowan knew about Benedict’s decision to resign back in December, a full month and more before most of the college of cardinals. What is going on here? Benedict’s attendance at Evensong in Westminster Abbey had a profound effect on his understanding of English religion, he simply wasn’t aware that this kind of catholic worship was a norm of English life. The choir was subsequently invited to sing at the Vatican. Rowan announced he would resign as Archbishop of Canterbury in March last year, taking effect in nine months. One can only conjecture at the effect that news would have had on the old man, but one shouldn’t ignore its possible influence on Benedict’s thinking about his own sensitive position. It would be even more fascinating to know what the two talked about in camera, and one day we may be fortunate enough to find out. I myself think that Rowan’s personal effect on Benedict is being underestimated. It is a fascinating moment in time in church history, and it has already happened, before our very eyes.

ReplyDelete