The "Fathers" and the Hermeneutics of Schism (The Strangeness of Scripture II)

The early Christian writers sometimes referrred to as the "Fathers" of the Church do not envisage an understanding of scripture implied by modern Protestant talk of “clarity” or “sufficiency”. Neither, however, do they imply the need for a sort of external ecclesiastical authority as the arbiter of truth for the average Christian.

Writers of the late second and early third centuries like Irenaeus, Tertullian, Clement and Origen all had to contend with groups who took scripture with enormous seriousness but whose interpretations were wildly different from their own - what we can call retrospectively "emergent orthodoxy". These others, most obviously those loosely termed "Gnostics", tended to wade through scripture with great care, using allegorical methods to claim support for elaborate cosmological myths.

The proto-orthodox response to the Gnostics was not to claim either sufficiency, or even the fairly obvious possibility of clarity, as a retort to the obscurity of these biblical speculations. Rather the early theologians I have mentioned assessed the adequacy of biblical interpretation by the doctrinal and ethical coherence of its results, with the “Rule of Faith” – effectively what we know as the Apostles’ Creed – as touchstone. Of course the Creed is itself largely derived from Scripture and indeed from what one might call its "plain" sense, so the questions of simplicity and accessibility are not irrelevant here.

Yet it was the Gospel, not scripture, whose clarity and accessibility to the simple as well as to the wise they affirmed. These early Christian writers acknowledged there were conundrums in scripture, some accessible only to the mature in faith, some just intellectually demanding, some utterly mysterious. Scripture was not all clear at all.

Yet while the Gnostics saw the capacity to probe these conundrums as a means of achieving spiritual maturity or power, the emergent orthodox rejected such a hierarchy of propositions and persons. While some, like Clement and Origen themselves, felt called to solve or at least probe these mysteries because of their calling as catechists or Christian philosophers, the basis of salvation was for them not knowledge of the answers, but reception of the gracious truth revealed to the poor and ignorant – not least the illiterate - as much or more than to the wise and powerful.

These early Christian writers all gave rather more room to the role of the Church as bearer of that Rule of Faith than some conservative Protestant hermeneutics would now allow.

One of the reasons for the emergence of a strong idea of scriptural clarity was the important realization on the Reformers’ part that the authority of Scripture could not and should not depend on the mediation of ecclesiastical authority. However nuanced it may now appear to be, official Roman Catholic pronouncements still tend to reflect the view that the magisterium of the Church, subsisting in a clerical hierarchy, retains an apostolic tradition of content and method necessary for adequacy of doctrine and interpretation.

The ancient Christian writers I have mentioned did not have this particular issue to contend with; for them, to insist on the place of the Church in the determination of genuine interpretation was not to invoke or even allow such an authority, but to insist that the community of the Church universal that confessed the Rule of Faith was the necessary context in which the adequate reading of scripture could take place.

To set the Fathers and the Reformers at odds here would simply be anachronistic. Yet we can and should ask whether the affirmation that the Gospel can be heard and believed by the simple, not least by reading scripture (otherwise unaided), requires or even allows the conclusion that the the personal act of reading, outside an ecclesial context, is really richer or more fundamental to hermeneutics than the communal act of hearing.

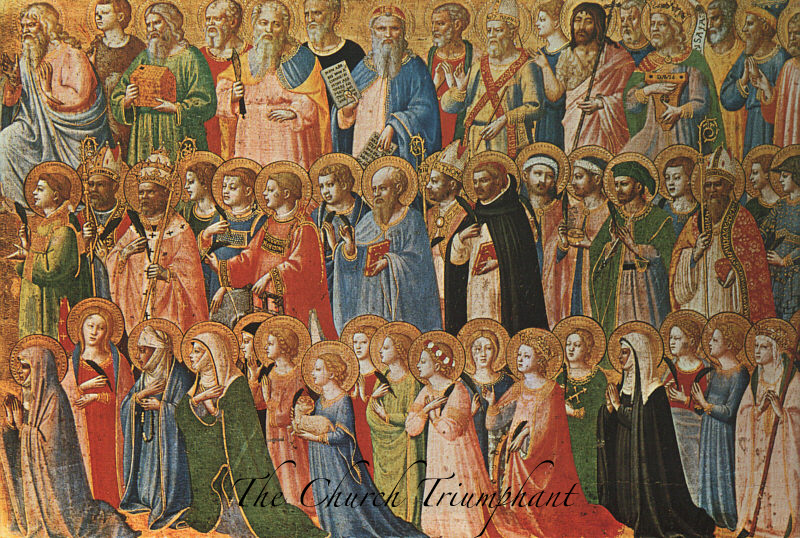

We can also ask whether the fullness of authentic interpretation can ever really be as well-served by schism in search of truth, as by persistence in service of unity. The fullness of interpretation is not the work of the most enlightened or Spirit-filled individual, but the rich, deep and challenging harmony of the action of the Word of God in the lives of all God's people.

This vision is inevitably eschatological - and I acknowledge there are circumstances where unity will appear impossible. Yet fundamentally intepretation is not enriched by isolated pursuit of the truth; schism should be acknowledged not only as regrettable, but as hermeneutically subversive.

Comments

Post a Comment